Our Lives in the Uncanny Virtuality

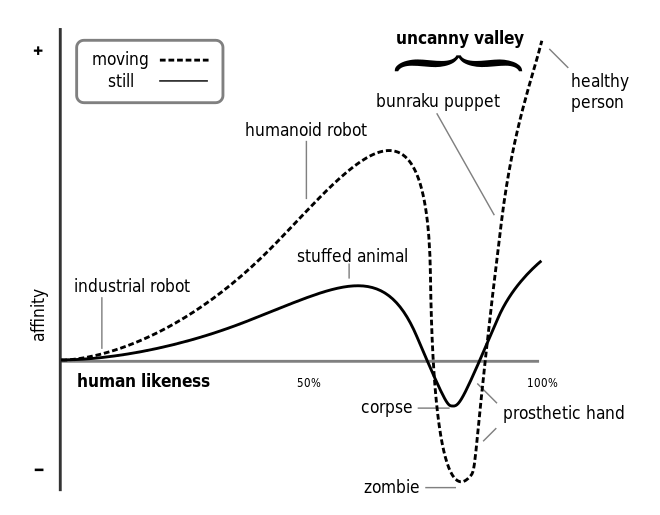

You may have heard of The Uncanny Valley, and you may have faced it more than once. The phenomenon was first coined and described by the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in an article published in 1970. Mori identified the phenomenon as bukimi no tani genshō, meaning ‘valley of eeriness.’ In 1978, author Jasia Reichardt translated the term’ Uncanny Valley’ in the book “Robots: Fact, Fiction, and Prediction.”

In his work, Mori noted that people found his robots more appealing if they looked more human. While people found his robots more appealing the more human they appeared, this only worked up to a certain point. When robots appear close to but not quite human, people tend to feel uncomfortable or even disgusted. Once The Uncanny Valley has been reached, people feel uneasy, disturbed, and sometimes afraid. What may happen when we cross the threshold and find ourselves immersed in it?

Exposure and Response to the Seemingly Real

Beyond robotics, with the increased use of CGI in movies kicked off by gargantuan blockbusters like Jurassic Park in 1993, dinosaurs and fantastic landscapes came to life before our eyes on the silver screen. With dramas like Forrest Gump, the obviously fantastic gave way to CGI that did not give us a clear signal for when something was recorded in the real, physical world or added in a seemingly real, virtual dimension. Before long, we were presented with audiovisual narratives on big, small and silver screens in movies, videos and games that did not pretend to make the fantastic realistic but to challenge our perception of reality.

In 2017, more insights emerged from further study of the Uncanny phenomenon at the Motion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory (EBBL) in the Department of Psychology at Tufts University. It showed that the Uncanny Valley not only triggered emotions and our mental alertness. The next natural step was how we react and behave towards what we perceive as trying to trick us. Entering The Uncanny Valley is not just a state of mind; it is also reflected in behaviour.

Inside the Internet

We have long surpassed the Internet as something we go to the desktop computer to visit. About a decade ago, during several presentations in the USA, as part of the launch of The Design Network, our team stated that the Internet is something other than what you go to visit. We were – and are – actually living in the Internet through our devices with and without screens as connection points. A phenomenon that was also coined as the Outernet.

Made possible by the Internet and everpresent by mobile devices, social media might be argued to be more about people being obsessed with themselves and attention than actually being social – which adds another meaning to the typical abbreviation SoMe (“so me” leaning towards “see me”), no one can argue its powerful influence on reality and the way people perceive and live their lives. Narratives, true or false, are continuously pushed at us and often accepted without a moment’s healthy scepticism.

Narratives, true or false, are continuously pushed at us and often accepted without a moment’s healthy scepticism.

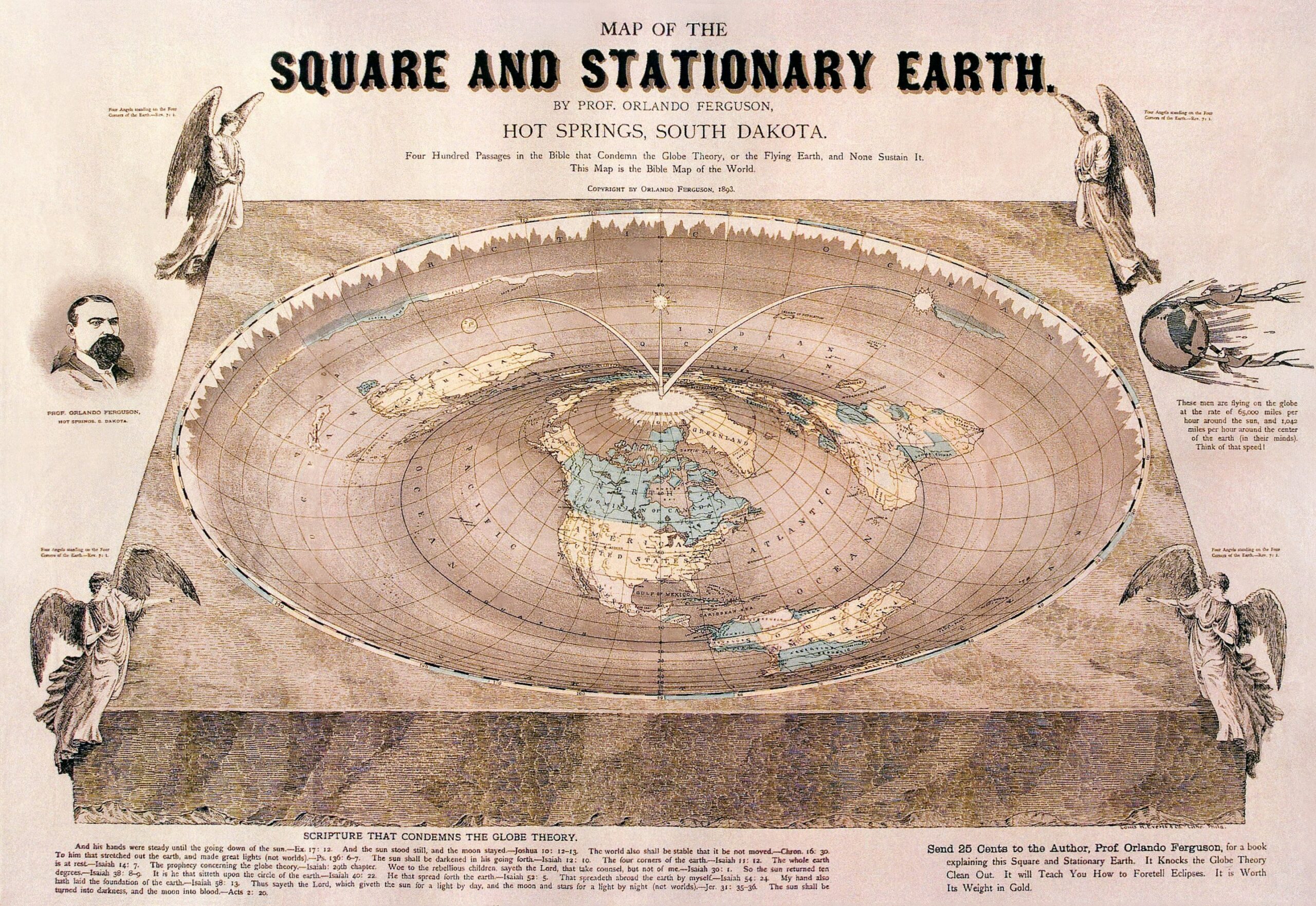

This presents us with a significant conundrum, as such narratives picked up without question sometimes make people question reality and breed distrust between people and peoples. Don’t believe everything you see on YouTube. Don’t do all the challenges presented on TikTok. Don’t think the person you just met on Instagram looks like that, behaves like that – or perhaps even exists. Unsurprisingly, people get suspicious about even the well-established and obvious and tend to gather in their small groups of like-minded people to get some assurance and confidence in beliefs rather than challenging their own established mindset.

Further Down the Slippery Rabbit Hole

Just as we have become inhabitants of an all-encompassing Internet, we no longer see the Uncanny Valley as just robots or events on a screen. We have ventured into it and have been surrounded by it for some time now. It has become our Uncanny Virtuality, where digital and physical realities collide and converge. What happens then, as the tools of generated and synthesized realities become widely available, so now seemingly everybody can create anything that makes it hard to differentiate fact from fiction. After all, handing everybody the giant megaphone that is social media was, in hindsight, not necessarily something we all were ready to handle.

After all, handing everybody the giant megaphone that is social media was, in hindsight, not necessarily something we all were ready to handle.

First, let’s get beyond the myth that everyone can create something with a single click. It takes more work to create something that stands out as more people access the same powerful generative tools. Just look at the state of generated creations. The lack of imagination and effort is showcased in the need for originality, often displayed in the use of AI tools such as Midjourney: /imagine how film x would look like if it were done by director x or /imagine if artist y had done painting y, anyone? Stuck on repeat, this is hardly the epitome of imagination; it is an exploration of features – which can admittedly be fun and entertaining.

Thriving in The Uncanny Virtuality

If storytellers, experience designers, moviemakers, communicators, brand managers, agencies, studios and the rest on the lengthy list of what we can give the common name creators do not want their work to become yet another brick in the walls of uncanniness, there are a few considerations to be made. Concerns that are very much about humanity, emotion and value. In The Uncanny Virtuality, people will be looking for something authentic, trustworthy and with a heart. Something that they will connect with, not because it was targeted towards them through pandering or to please them, but because the dormant connection already exists on a deeper level. Not everything said and done may be perfect, but it is honest and relatable.

At the core of the matter, it comes down to the question of establishing a healthy virtuality culture. Doing so includes thoughts on what kind of ethics and narratives we want to explore and share and how they reflect who we are and what we aspire to be, whether in a digital or physical reality – or an amalgamation of both. Luckily, there is inspiration out there for establishing an authentic culture. Such as what can be learned from progressive museums that help us understand our past, present and future by balancing cultural heritage, engaging storytelling, and innovative interpretation without losing their own voice, authenticity or credibility. To thine own self be true.

In conclusion, there may yet be hope that we do not get lost in our newfound Uncanny Virtuality. It will not happen if we try to make our way through it, blinded by irrational fear or naive infatuation. As has been the case with so many other technological milestones in human history, as we move forward, we need to learn more with each careful step we take, and without forgetting to look at our compass of morals and humanity once in an ever so often while.